Easter fun at the museums!

Exhibitions, trails and activities; six fun things for all the family to enjoy at The Beaney and...

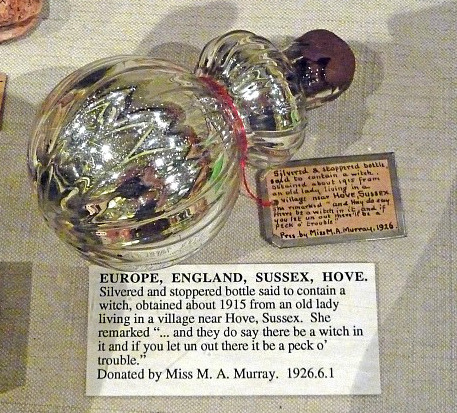

However an artefacts questionable provenance can add to its appeal; for example, arguably one of the most interesting objects in the Pitt Rivers collection in Oxford is a small bottle with a label that reads ‘said to contain a witch’, it’s place in the collection based solely on the affirmation of a single individual. Another object destined for a future collection came about sometime in the 1990’s; one in a range of free toys produced by a fast food outlet; a small pot that once opened was said to release a ghost trapped inside, one of these pots that has never been opened is now a prized piece of memorabilia.

The artist Piero Manzoni, most famous for tins containing a different sort of human remains explored the idea of the fetishisation and commodification of his own bodily substances. When talking in 1960 about one work ‘Artist’s Breath’ Mazoni said; ‘When I blow up a balloon, I am breathing my soul into an object that becomes eternal’.

Like Manzoni’s artworks and the trapped ghost, the hair of the French Emperor is also both artefact and commodity; in a 2015 auction in Dorset, a single strand of Napoleon’s hair, cut from his head in 1816 was sold for £130. On average a person with brown hair has around 100,000 strands and Napoleon was reported to have his hair cut ‘very frequently’. At £130 a strand, even taking into account the hair loss of the average middle-aged man and an effective flooding of the market, the descendants of Napoleon’s barbers could have been very rich indeed.

(One can only imagine the sort of interest the auction of Van Gough’s ear might create if it had been pickled after being severed in 1888 but at the time no one could possibly have known that the ear would become an unintentional icon of art history with its own BBC documentary.)

Napoleon’s hair may be lost but Canterbury Museums and Galleries are still home to a number of other very interesting human remains. Hair comes in lockets, souls in balloons, witches in bottles, ghosts in pots and at the Canterbury Roman Museum; bones in helmets and in jars. One of the most important artefacts on display at the museum is an Iron Age helmet that was found in Bridge in 2012 and dates back to the time of Julius Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 54BC. Apart from its rarity, being the best example of its kind found in Britain, there was something else that astounded archaeologists; inside the helmet, which was found buried upside down, were cremated human remains. The helmet had been reused as a burial urn. What complicated debate around this important find however came after further examination of the remains which turned out to be not those of a male soldier either fighting against or alongside the Roman army but those of an Iron Age woman. The remains can be seen today alongside the helmet at the museum where you can learn about the various interesting theories relating to this unique discovery.

Elsewhere in the museum you can see Roman glassware, reused as burial urns, discovered with the human remains still inside. Also in the collection are artefacts from a hastily dug grave of two Roman soldiers that Archaeologists believe to be evidence of a concealed murder that took place in the city almost 2000 years ago.

If visiting the Beaney House of Art & Knowledge this October, you can see the Latham Centrepiece* (or the Albuhera Group), the last chance to see the item in Canterbury before it returns to its permanent home at the National Army Museum in London. The late nineteenth-century silver centrepiece depicts a seminal moment in the battle of Allbuhera in 1811 in which Matthew Latham, Lieutenant of the Buffs, lost his arm; cut off by the attacking French Calvary. Latham somehow managed not just to survive his considerable wounds but to save the regimental flag from French capture. Alongside the centrepiece at the Beaney you can see not the severed arm of the Lieutenant but other evidence of gruesome Napoleonic warfare; a letter from Buffs Captain Joseph Fenwick that he wrote in battle in 1810 using his own blood in lieu of ink.

So at this time of year, if looking for the morbid and macabre; you can find it in museums.

Written by Murray O’Grady, Visitor Service Officer, Canterbury Roman Museum